The Most Supreme Criminal Act in The History of Psychiatry

- sylvia True

- Aug 23, 2020

- 2 min read

My brothers and I spent the summers in my grandmother’s Swiss chalet in Arlesheim. We would sit at the round dining room table covered with an ironed linen tablecloth as my grandmother would watch us and score our manners in her small spiral notebook. Each meal began with a clean record and an amount of one franc. Every infraction—not holding a fork correctly, moving the spoon in the wrong direction while eating soup, not sitting up straight—resulted in deductions. For the most part, my brothers and I considered it a game, although that was far from my grandmother, Omama’s, vision.

She sat tall, her chin lifted, her lips pressed together, and her ankles crossed, as she judged. During one dinner, my gaze shifted to Omama’s desk, neat and tidy, and perfectly dusted. On top of the desk stood a miniature oil painting framed in ornate gold. For many years I had wondered who the painting was of, but with the intuition of a child, I knew not to ask. The woman wore a long, flowing red gown. Her hair was swept up elegantly, and her eyes were cast slightly downward. I had always wanted to know who she was, and on this particular evening, I gathered enough confidence to ask.

“Omama, who is the lady in the picture?” She put down her pencil and bristled. “That is my sister.” Her voice was distant.

“I didn’t know you had a sister,” I replied. I wanted to stand, walk to the desk and take a closer look, but that would have cost me my entire franc.

“I did,” Omama said.

“Oh.” I knew she didn’t want to say more, but still, I pressed. “Does she live around here?”

Omama slapped her hand on the table. “Of course not. She is not alive.”

“Oh,” I said meekly. “How…”

“Influenza.” And the subject was closed.

But I never stopped wondering. A few years later, I asked my mother about the woman in the painting and her reaction, not untypically, was one of distress. She rubbed her eyebrow, as she claimed that she had no idea what I was talking about.

So it was dropped. And it would have remained buried if I hadn’t gotten myself admitted to McLean psychiatric hospital for major depression with psychotic tendencies. Initially, both my mother and Omama were too terrified to speak to me. Eventually, though, bits and pieces of a traumatic history began to slip out.

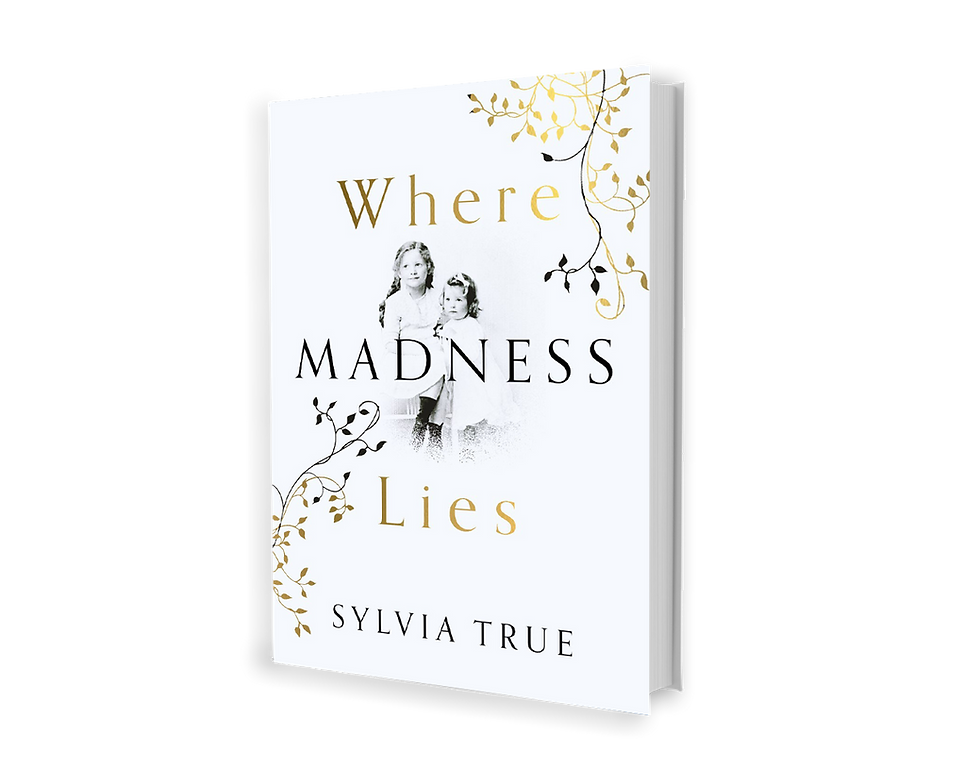

The woman in the picture was my Omama’s younger sister, Rigmor. In her late teens, she was diagnosed with hysteria, not considered especially terrible. But as she continued to worsen, the diagnoses began to stack up.

Rigmor and my grandmother lived in their family home on the wealthiest street in Frankfurt am Main. Although they were Jewish, they didn’t practice the religion and thought of themselves as German. Perhaps if they would have left Germany in 1934, they could have done so with their family intact.

Comments